We seem to be at another crossroads for the Me Too movement, with high profile allegations lodged against a number of celebrities. The horror community has been impacted by the disturbing and quite serious accounts of sexual abuse and harassment involving Cinestate, the company that produces films and owns Rebeller, Birth.Movies.Death, and Fangoria. The Cinestate allegations, brought to light by a well reported exposé on The Daily Beast, sent ripples across the horror community, not just regarding the ensuing collateral damage but the idea of believing survivors and the notion of whether or not the horror community is truly welcoming for all.

It’s a valid concern, especially given the large number of women, minorities, and LGBTQ people who are fans of horror or work in the genre themselves. It’s no wonder that women, especially, are drawn to horror, given the focal role women often play in these narratives. I’m reminded particularly of two films that deal explicitly with the oppression and manipulation of women: Michael Winner’s The Sentinel (1977) and Rob Zombie’s The Lords of Salem (2012).

Women have historically been threatened in horror films, but the lead character in The Sentinel has an exceptionally rough time of it. Alison Parker (Cristina Raines) is a fashion model who moves into a Brooklyn Heights brownstone that turns out to be hiding a sinister secret: it contains the entrance to Hell. Alison has had a rough life, having withstood a horrible relationship with her adulterous father, suicide attempts, and an affair with married lawyer Michael (Chris Sarandon), whose wife died under murky circumstances. Shortly after Alison moves in, she’s greeted by a number of odd neighbors who demand increasingly large amounts of her time, and she’s plagued by nausea and fainting spells. It’s as if multiple forces have unseemly designs on her, but to what end?

The Sentinel is a strange, idiosyncratic movie, a gloss on the classic Rosemary’s Baby with a more low rent sensibility—but it’s undeniably effective. Populated by a stunning array of talents and character actors—everyone from Ava Gardner to Burgess Meredith to Christopher Walken—and lurid shocks, The Sentinel is a narrative with a “protagonist” maybe even more helpless than the doomed Rosemary. That character fought hard to escape her horrifying predicament, even if it was ultimately a losing battle, but Raines’ Alison is extremely passive, a character who is essentially swept along by the bizarre cast of characters and disconcerting events. In her commentary for the 2015 Scream Factory edition of the film, Raines called herself “more of a prop.” (Raines also indicates that she herself suffered on-set thanks to director Michael Winner: “It was just a really unpleasant experience working with him, in all honesty.”)

In a flashback scene Alison’s father hits her repeatedly after she walks in on him with a pair of prostitutes, driving her to attempt suicide; when a lesbian tenant starts masturbating in front of her over tea, Alison just looks away and squirms uncomfortably; and near the end, she hastens back to the apartment as if pulled by some invisible force. At the climax, she’s given a “choice”: give in to the infernal intentions of her demonic neighbors and descend into Hell with her boyfriend, who’s revealed to have had his wife murdered, or accept the role of the new guardian against Hell for the Catholic Church—by becoming a blind, miserable nun for the rest of her earthly existence. Arthur Kennedy’s Monsignor Franchino, the architect of this whole affair, posits the assignment as the way her soul, damned for her repeated suicide attempts, can be saved. Not much of a choice at all, really.

The scenario is a sort of inversion of the Rosemary’s Baby plotline—this time the forces of God want to exploit a vulnerable woman for their own ends. (The Catholic Church’s depiction as a sinister, secretive organization isn’t so far-fetched when you consider the revelations of sexual abuse and cover-ups in the church that surfaced years after the movie’s release.)

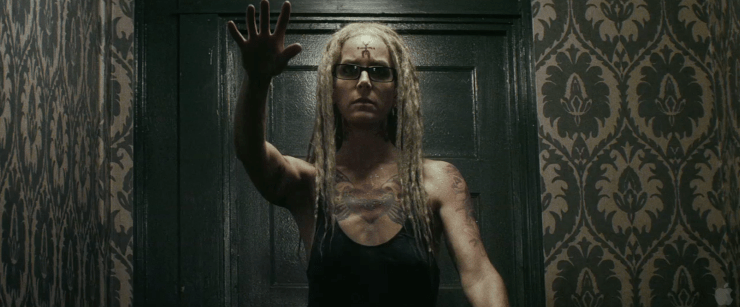

Similarly, radio DJ Heidi Hawthorne (Sheri Moon Zombie) in The Lords of Salem finds herself a helpless pawn of forces beyond her control. The descendant of a judge in the Salem Witch Trials, Heidi finds herself the target of a centuries old coven of very real witches in contemporary Salem. Much like Alison, Heidi has a troubled past—she’s in recovery after a heroin addiction, so when she starts to experience attacks and hallucinations stemming from a cursed vinyl record, her cohosts at the station can’t help but suspect she’s fallen back on old habits. By the time she does in fact relapse, it’s become clear to Heidi, and the audience, that there’s little she can do to extricate herself from the witches’ plan.

Like Alison, Heidi has ingratiating but malicious neighbors and an apartment building that seems to contain a portal to Hell. In the ambiguous, hallucinatory finale, Heidi has been decked out in royal finery onstage at a “concert” for the makers of the record, while a news report epilogue indicates that all the women in the audience (also descendants of Salem villagers) were found dead, while Heidi has vanished.

Both of these films have bleak endings for their central characters. But in highlighting the mistreatment and abuse suffered by their female protagonists, they shed light on a very real dynamic through an exaggerated supernatural lens. Women may not be recruited as sentinels or harbingers of evil, but they are all too often abused and traumatized, misled by men or systems put in place ostensibly to protect them. They are groomed by sexual predators. Their past experiences are used to cast doubt on them when they speak up about abuse. Their morals are called into question. In The Sentinel, Alison confesses to Franchino that she’s “committed adultery” with Michael, and attempted to take her own life, and the Monsignor responds sympathetically, promising that returning to Christ will save her. But he’s been systematically setting her up as the next Sentinel, ultimately using her sins to blackmail her into doing the Church’s bidding. Rather than offering her support and guidance for the immense pain that led her to attempt suicide, he manipulates her into accepting a thankless job and a new, chaste identity. Alison is punished for her sexuality and pain—for her very humanity. In the final scene, she looks just as ghoulish as one of the demons, holding a heavy cross and staring sightlessly out of a window. Similarly, Heidi’s eyes in the finale of The Lords of Salem appear white and sightless, and she is posed like a religious statue.

This is what women in these cautionary tales are reduced to—props to be controlled and exploited as others see fit, denied their agency and identity. It’s why these larger than life horror stories remain intriguing and powerful in our confusing and frightening reality. I look forward to seeing new stories with happier endings for women—in both cinema and the real world. But in the meantime, these films are fanciful yet potent reminders of the dark forces women encounter every day.

source https://bloody-disgusting.com/editorials/3623780/prop-forces-darkness-women-sentinel-lords-salem/

No comments:

Post a Comment